Dopamine, a neurotransmitter often associated with motivation and goal-directed behavior, plays a key role in how students engage with learning.

When students anticipate progress, feedback, or meaningful rewards, dopamine activity increases, reinforcing behaviors linked to positive learning outcomes.

This neurological mechanism is particularly relevant in today’s online K-12 classrooms, where digital tools and gamified elements are frequently used to shape student engagement.

Dopamine and Motivation: The Neuroscience Basics

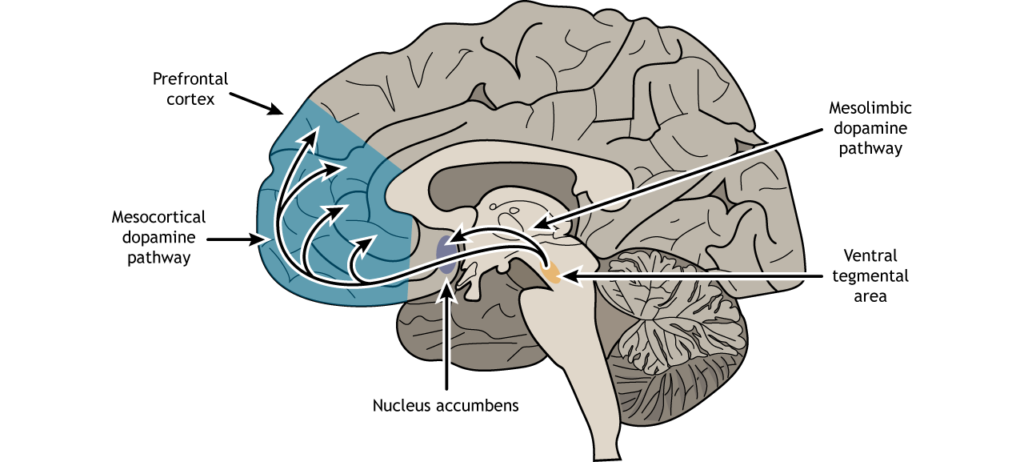

Dopamine operates through several interconnected neural pathways, most notably the Mesolimbic and Mesocortical pathway, which are central to motivation, learning, and decision-making.

Image source: pressbooks.pub

These pathways originate primarily in the ventral tegmental area (VTA), a midbrain structure that releases dopamine to multiple regions involved in evaluating outcomes and guiding behavior.

In the mesolimbic pathway, dopamine projections to the nucleus accumbens help the brain assign value to experiences, reinforcing behaviors that are perceived as beneficial or rewarding.

(Source for the last 3 paragraphs)

Importantly, dopamine does not simply produce feelings of pleasure.

Instead, it acts as a learning signal by encoding reward prediction error (the difference between expected and actual outcomes).

Most dopamine-producing neurons increase firing when outcomes exceed expectations (positive prediction error), maintain baseline activity when outcomes match expectations, and decrease firing when outcomes fall short (negative prediction error).

This means that when results are better than anticipated, dopamine activity increases, strengthening the neural connections linked to the preceding behavior.

When outcomes fall short of expectations, dopamine signaling decreases, prompting the brain to adjust future actions.

This shifting activity helps the brain update future expectations and reinforce adaptive behavior.

Through this continuous feedback loop, dopamine helps the brain update expectations, refine strategies, and regulate motivation over time, making it a fundamental neurochemical driver of learning and adaptive behavior.

(Source for the last 7 paragraphs)

These dopamine-driven learning signals operate continuously, shaping how students respond to feedback, challenges, and progress cues throughout the learning process.

Student Engagement in Online K‑12 Classrooms

Online K-12 learning environments that operate without regular tutor interaction face distinct engagement challenges, including social isolation, passive content consumption, and limited opportunities for real-time feedback.

Without these interactive elements, sustaining student motivation can be particularly difficult.

This is why, even as an online school, at EduWW we take tutor support, among other things, very seriously.

Gamification has emerged as one strategy to address these challenges by introducing structured feedback and a sense of progression.

Features such as progress bars, badges, leaderboards, and goal-based missions create clear signals of advancement, helping students track effort and outcomes over time.

From a neuroscientific perspective, these mechanisms align with dopamine-driven learning processes by reinforcing goal-directed behavior and sustaining attention through timely feedback.

Research suggests that well-designed gamified online classrooms are associated with higher participation rates, improved attendance, and better content retention, as motivational signals encourage students to remain engaged with learning tasks.

Gamified Reward Systems: How They Stimulate Dopamine and Drive Behavior

There are multiple ways to simulate this type of behaviour.

Reward Mechanics

These can be:

- Points and Badges: Each accomplishment triggers a dopamine release, reinforcing motivation.

- Leaderboards and Competition: Social comparison amplifies the incentive to “win,” fueling further effort.

- Progress Bars and Unlocking Content: Observable advancement encourages persistence.

Dopamine Anchoring

This approach involves pairing effortful or less immediately engaging tasks with a consistently positive stimulus, such as background music, brief breaks, or other enjoyable cues.

Over repeated exposure, the brain begins to form associative links between the challenging activity and the anticipated positive experience, which engages dopamine-related motivational systems and makes task initiation and continuation more likely.

Dopamine’s role in signaling reward anticipation and guiding motivated behavior is well established in neuroscience research, where neurons increase firing when expected rewards are predicted based on prior associations.

(Source for the last 3 paragraphs)

This kind of strategy, sometimes referred to in applied learning contexts as dopamine anchoring, reflects how anticipated positive outcomes become tied to the act of engaging in a task, rather than merely the outcome itself. Dopaminergic signaling supports learning about these cues and their motivational significance.

To simplify this, “dopamine anchoring” describes how the brain associates starting a task with the expectation of a positive outcome, increasing motivation even before the reward is experienced which makes a person more willing to start and persist with effortful work.

(Source for the last 2 paragraphs)

While this strategy can support short-term engagement and help with habit formation, experts caution against over-reliance on external stimuli.

Research across educational psychology and motivation science shows that excessive dependence on extrinsic rewards (such as tangible incentives) can reduce or “undermine” intrinsic motivation, the internal drive to engage in an activity for its own sake, a phenomenon documented in both behavioral and neural studies.

While dopamine anchoring can support short-term engagement, particularly for K-12 students who receive frequent feedback such as grades or teacher evaluations, over-reliance on these external rewards can limit the development of intrinsic motivation, the internal drive to engage in learning for its own sake.

In later stages of life, where rewards and feedback are often delayed or less predictable, individuals who depend primarily on extrinsic reinforcement may struggle to maintain motivation.

For example, pursuing a long-term goal like starting a business or building a career may take months or years without immediate feedback.

Without strong intrinsic motivation, sustaining effort over such extended periods can be challenging.

Novelty and Adaptation

Introducing gamification often leads to an initial spike in student engagement, but this effect can diminish over time due to the novelty effect.

Neuroscience research suggests that dopamine-driven motivation is particularly sensitive to new or surprising stimuli, and repeated exposure can lead to habituation, reducing the reward signal associated with the gamified element.

However, although studies indicate that engagement tends to decline after a few weeks, the familiarization effect can get it back on track.

The familiarization in gamified experiences can even be recovered and further accelerated by evolving, diversifying, or adapting to the learner’s progress. (Source)

Online learning platforms that refresh content, vary challenges, or personalize tasks help maintain anticipation and perceived value, sustaining motivation over the long term.

The Balance: Extrinsic vs. Intrinsic Motivation

Gamification is often associated with external, or extrinsic, rewards—such as points, badges, and leaderboards—which are designed to reinforce participation and performance.

When thoughtfully integrated with core principles from Self-Determination Theory (SDT), namely competence, autonomy, and relatedness, gamified learning environments can also support intrinsic motivation, the internal drive to engage in learning for its own sake.

However, some studies also note that gamified learning can have little to no impact and even hinder the intrinsic motivation. Even though gamified elements overall help students learn better, the intrinsic motivation part is highly debated.

(Source for the last 3 paragraphs)

Thoughtful design, with meaningful challenges that are focused on teaching in a fun way, helps preserve student autonomy and intrinsic interest.

Potential Pitfalls and Ethical Considerations

Gamification Overuse and Misuse

While gamification can boost initial engagement, an excessive focus on points and rankings may shift learner attention away from deeper educational goals.

Systematic reviews of educational gamification have documented cases where badges, leaderboards, or points were associated with motivational issues or reduced performance when misapplied.

(Source)

Diminishing Returns

Longitudinal research supports the novelty effect in gamified learning: initial positive effects often diminish over time as students become familiar with game elements, indicating that static reward structures can lose their motivational impact.

(Source)

Individual Differences

Moreover, studies find that not all learners respond equally to gamification.

Research based on personality traits shows differential engagement, and recent work suggests that adaptive gamification strategies tailored to individual preferences tend to sustain motivation better than one-size-fits-all designs.

(Source)

Conclusion

Gamified online K‑12 classrooms harness the power of dopamine to enhance student motivation and engagement.

By structuring learning with incremental rewards, progress visibility, social interaction, and adaptive challenges, educators can create a positive loop: students feel good about learning, dopamine reinforces engagement, and learning becomes more self-perpetuating.

However, to be sustainable, gamified systems must:

- balance extrinsic and intrinsic motivation;

- avoid overemphasis on superficial rewards;

- evolve over time to counter novelty fatigue;

- Accommodate individual learner differences.

When implemented thoughtfully, gamification, rooted in our understanding of dopamine and reward psychology, becomes more than just a game: it becomes a motivational scaffold that supports meaningful, enduring learning.